The Chesapeake House by Cary Carson

Author:Cary Carson

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The University of North Carolina Press

Published: 2013-10-14T16:00:00+00:00

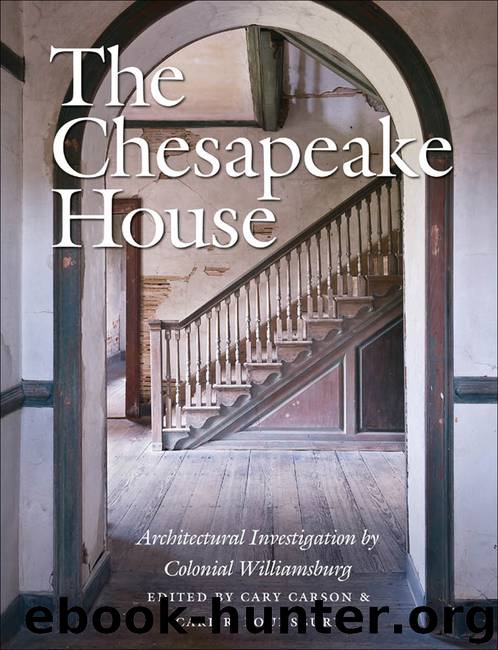

Fig. 11.16. Carter’s Grove, 1751–55, James City County, Virginia.

In the early 1750s, at Carter’s Grove, Nathaniel Burwell’s plantation near Williamsburg, bricklayer David Minitree embellished the two-story brickwork with delicately attenuated gauged and rubbed jack arches in every aperture on the building, from the cellar to the second story (Fig. 11.16). The aperture openings on the two main stories were identical in size and maintained a two-to-one ratio of height to width. The craftsman lightly rubbed the jambs on both stories. He emphasized the hierarchy of the stories by building shorter jack arches on the cellar apertures, which also blended more closely with the color of the plinth bricks. The rich red bricks of the second-story jack arches extend four courses in height, compared to the five courses of the main story. Typical of many craftsmen in the region, Minitree created the angle of the splay of the voussoirs of the jack arches by measuring from a point below the center of the opening that was equal to its width. This method resulted in a splay roughly 63 degrees at the end of the flat arch.30

He capped the plinth with a three-course molded water table. A Flemish-bond cavetto course sits atop a double row that forms a torus, all of which are rubbed and laid in wafer-thin, limed putty joints. However, Minitree muted the contrast between the water table and the walls by choosing bricks of a similar color range. The precision of the water table is matched by a three-course rubbed stringcourse with the same narrow joints. The stringcourse stops short of the lightly rubbed corners. The entrances on both the land- and the river-sides of Carter’s Grove are marked by pedimented frontispieces whose gauged bricks are rubbed a deep red and whose thin joints were covered with a red wash. Minitree’s work represents the epitome of late colonial workmanship.

Yet, within a generation, the contrast coloring at Carter’s Grove was beginning to lose favor. After the Revolution, fewer patrons chose to augment their buildings with gauged and rubbed stringcourses, water tables, and frontispieces. However, rubbed arches remained a staple of the bricklayer’s art through the second or third decade of the nineteenth century, and the uniform color of the brick walls became the new aesthetic cynosure. In the 1790s, V-shaped joints began to supersede scribed ones as the preferred decorative mortar finish, a gradual switch that occurred over the next thirty years (see Fig. 11.5C).

Because far more buildings survive from the late colonial and early national periods, there are a number of recognizable differences in the bricklayer’s art in Virginia and Maryland. This geographic division is not rigid, however, as brickwork in some areas of Virginia that border the Potomac River and the Eastern Shore display certain affinities with patterns that became common in Maryland. Conversely, the brickwork in sections of southern Maryland appears nearly indistinguishable from that of its southern neighbor. As was probably true of the previous century, much more united the work on both sides of the provincial boundaries than divided it.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15365)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14522)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12405)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12101)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12036)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5795)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5454)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(5411)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(5312)

Paper Towns by Green John(5195)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(5013)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4967)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(4508)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4493)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4451)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4398)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4353)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4330)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4207)